Usually, for a product or process to infringe a patent, it must include every feature of at least one independent claim of the patent.

But, can you catch a patent infringer who skirts around the literal wording of the patent claims? In some jurisdictions, yes. A product or process may still infringe a patent even if it omits a claimed feature, interpreted literally, if it instead provides an equivalent of that feature. In the UK, the leading judgement on this is Actavis v Lilly, which opens the door for patentees to assert that immaterial variants could fall within the claim scope. However, the recent UK High Court decision in Salts Healthcare Ltd v Pelican Healthcare Ltd [2025] EWHC 497 (Pat) adds nuance and offers a timely reminder: not all equivalents lead to a finding of infringement. In this article, we explore why functional equivalence did not quite catch the alleged infringer this time.

Background

Salts and Pelican are bitter rivals in the healthcare device market. Salts alleged that Pelican’s ModaVi ostomy bags infringed its UK patent (GB 2569212 B), specifically claims 5, 8, and 20. These claims recite a colostomy appliance comprising at least two weld portions, each extending away from a periphery of the appliance and downwardly towards a bottom of the appliance.

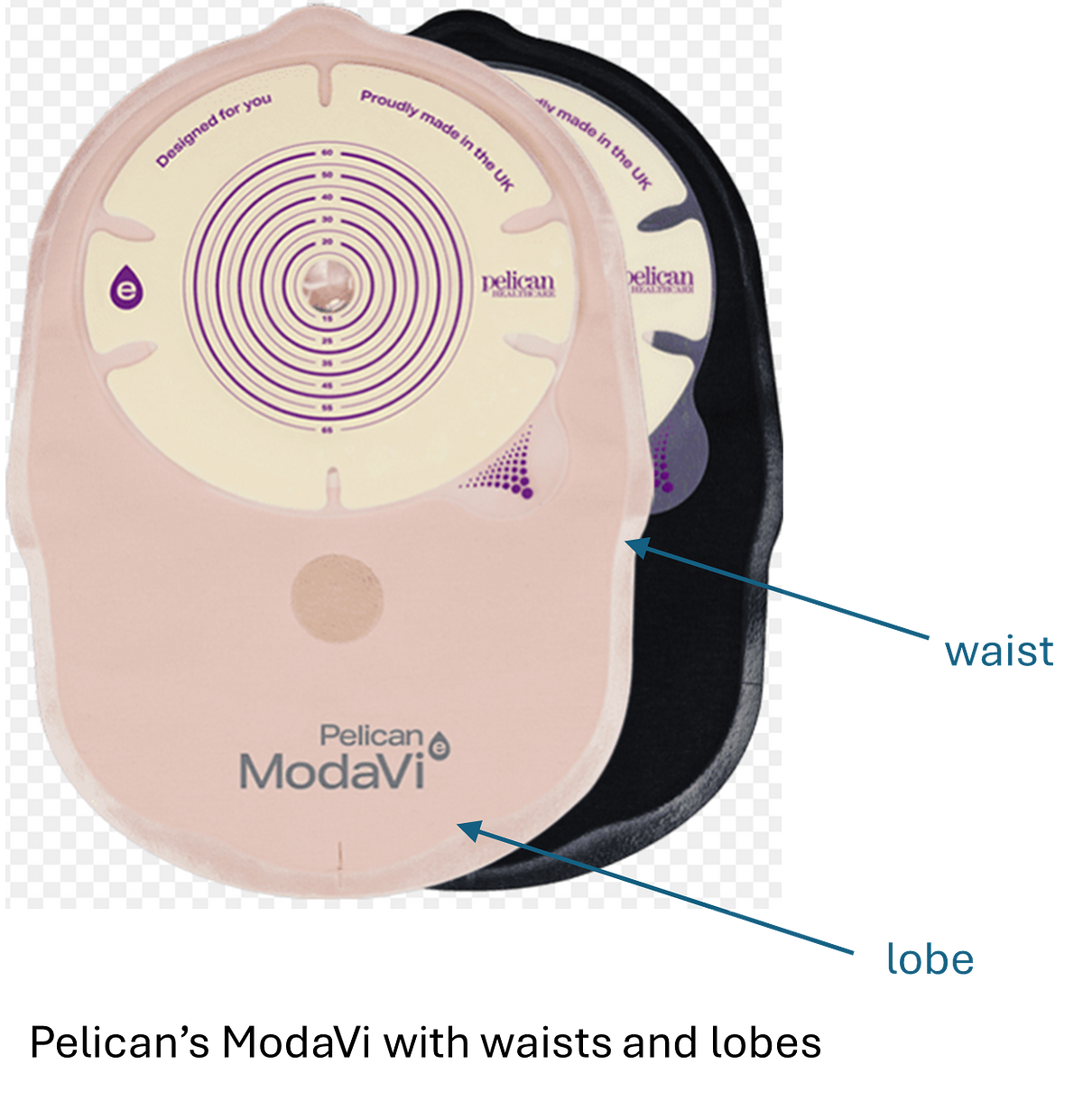

Salts argued that the ‘waist’ and ‘lobe’ features of Pelican’s ModaVi product could be interpreted as those weld portions, bringing the product within the scope of the claims.

The Judgment

The judge interpreted the claimed ‘weld portion’ as a weld that ‘connects the front of the bag to the back’. He further considered the weld is ‘part of or additional to the peripheral connection, and points down towards the bottom of the ostomy bag’. Functionally, the welds serve to minimise bulging or pulling at the wafer as the bag fills.

On examining the ModaVi device, the judge concluded that the ‘waist’ was not a weld that extended downwardly nor away from the bag’s periphery. While he accepted that the ‘lobe’ extended away from the periphery, he found that it did not extend downwardly. As such, ModaVi did not fall within the normal, purposive interpretation of the claims.

But what about functional equivalence?

Applying the three-stage test for infringement by equivalents set out in Actavis v Lilly, the judge answered ‘yes’ to the first two questions: Does the variant achieve substantially the same result in substantially the same way as the invention (yes), and would this be obvious to the skilled person at the priority date (yes).

Based on experimental evidence, the judge agreed that the ModaVi lobes affected the shape of the bag in a way that minimised bulging and pulling, much like the claimed welds. See a comparison between Salt’s own product ConfidenceBe having the claimed weld portions vs Pelican’s ModaVi having waists and lobes.

However, on the third question, the judge also answered ‘yes’, and this proved fatal for Salts. That question asks: Would a skilled person conclude that the patentee intended that strict compliance with the literal meaning of the relevant claim(s) of the patent was an essential requirement of the invention?

The judge found that strict compliance was indeed intended. In his reasoning, he noted that Salts chose to claim specific structures to achieve the desired effect. It would have been straightforward for Salts to formulate a claim by result or to a ‘narrower’ bag or to omit the word ‘downwardly’, but they did not. The claims were found to be intentionally limited to the structural features described. As a result, infringement by equivalents failed.

Our comments

This outcome may seem harsh on the patentee, especially given that the judge accepted the patentee passed two-thirds of the Actavis test. But the judgment in Salts v Pelican is not a one off. In Well Lead Medical v CJ Medical, the patentee also stumbled on the final hurdle.

In Well Lead, the court similarly accepted that the alleged infringer’s product, despite having different diameters, achieved the same result in substantially the same way as the patent and it would have been obvious to the skilled person. However, a passage in the patent description states: ‘According to the present invention, the diameter of the [side arm lumen] is the same as the diameter of the [sheath lumen]…’. This was taken to indicate that the patentee intended strict compliance, requiring the diameters to be the same. Once again, infringement by equivalents was therefore rejected.

These judgements offer a reminder that infringement by equivalents is not always a safety net to the patentee. Even if an infringer adopts the patentee’s inventive concept, they may still escape liability. Or, to borrow the lesson from Salts v Pelican: the functional similarities between the welds and the lobes couldn’t save the day; not all welds are gold.

Clearly, claim drafting matters. More thoughts should go into formulating patent claims that capture functional equivalents and foreseeable design-arounds. The patent description should also be crafted carefully to avoid any indication that strict compliance with the literal meaning of the claims is essential.

Perhaps it is also worth explaining why the invention works. Notably, in the patent document, Salts does not explain the principle or rationale of the weld portions. While the judgment does not explicitly say so, the lack of teaching may explain why the judge felt a strict compliance with the patent claims is necessary. By contrast, in Actavis v Eli Lilly, infringement was ultimately established. In Actavis, although the patent claims recite ‘pemetrexed disodium’, the specification goes further to describe a broader antifolate usage and explains ‘the use of vitamin B12 in combination with an antifolate reduces drug toxicity without adversely affecting antitumor activity..’. To this end, other salt forms (e.g. pemetrexed dipotassium) were found to infringe the patent by equivalence. That patent therefore effectively protects the core inventive concept, not just the specific sodium salt form. This may suggest including a little more insight about why the invention works could have gone a long way in supporting a broader interpretation of the patent claims.

Author: Julia Li

Further advice

For further advice, please contact the team at Hindles.